The Manitoba Schools Question

On January 29, 1895, a major political event marked political debate and Laurier’s prestige across Canada. The electors discovered the extent to which Laurier was a man of compromise and negotiation.

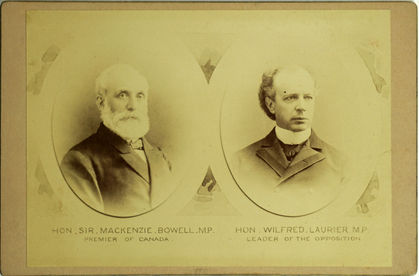

In 1890, the Greenway government in Manitoba imposed a non-denominational educational system on all citizens of the province. This new law contravened the principles of the Canadian Confederation. The Conservative government of Mackenzie Bowell sought the opinion of the Privy Council’s judiciary committee regarding the province’s legal ability to act in this manner. The committee was also questioned regarding the government’s power to intervene.

In January 1895, the committee confirmed that the federal government was entitled to intervene in the Manitoba decision to withdraw the right to a Catholic education from the French Catholic minority.

The federal government elected to enter the debate. Bowell’s Conservatives wanted to intervene in a matter of provincial jurisdiction and Laurier was resistant to the idea. His Liberal troops were divided on the subject, as was Laurier. Given his values, Laurier opposed the decision because the law was undemocratic and unconstitutional. His French Canadian origins prevented him from thinking otherwise. However, from a strictly legal point of view, he agreed with his opponents’ outlook: the federal government had no business interfering in the debate. Education was a matter of provincial jurisdiction.

Laurier chose not to take a firm stand in the matter, although he was sympathetic to the populations affected. During debates, he used the spirit of Confederation to support his point, highlighting the importance, in debate, of protecting Catholic and Protestant minorities and linguistic diversity.

Knowing that his own party’s unity was at stake, he chose to take advantage of the dissention within the Conservative Party to win the battle. While drawing attention to the dissention among his adversaries, he sought to avoid drawing attention to the rifts within his own party.

On February 11, 1896, the Liberals tabled draft remedial legislation to re-establish ― in principle and in practice ― separate schools in Manitoba. Although Laurier doubted success, he sought to buy time. He wanted to prevent a decision favouring non-denominational education from being reached prior to the next elections. Likewise, he wanted to avoid voting against the majority of his electors in western Canada. This position clearly demonstrates the extent to which Laurier sought to satisfy minorities without positioning himself against the majority. The debates were long and lively. Each stuck to his position. The draft law on Manitoba schools was deferred on April 14, 1896 owing to Opposition obstruction. On April 24, the federal government announced federal elections on June 23. Bowell tendered his resignation and was replaced by Charles Tupper who became Prime Minister on May 1, 1896.

The debates of 1895 on the Manitoba schools question allowed Laurier to assert himself as the defender of all Canadians. He succeeded in establishing his leadership over his troops prior the election of June 1896.